This is part three of a 10-part series exploring each of the Yamas and Niyamas to discover how we can incorporate them both on and off the mat for a deeper, richer life of yoga.

In 800 AD, boats carrying Polynesian settlers from land more than a 1,000 miles away, beached on a small island in the South Pacific. There, they found the resources to be abundant. They cut down trees to make way for agriculture, created a thriving community, and over hundreds of years the island came to support thousands of inhabitants. Yet when European explorers arrived on the island the day of the Easter holiday in 1722, they found no signs of life—only barren land, dotted with giant stone monuments that gave clues to the once-vibrant civilization that lived there.

We don’t imagine ourselves to be thieves. There’s not a “swag bag” on our backs, stuffed with the family silver from the house down the road. We’re not holding up banks, or pick-pocketing on city streets. Yet, asteya, the third of the Yamas and Niyamas in the eight-limbed path of yoga, reminds us that we are always taking. From the minute we are born into the world—air, food, wood, sunlight, water, help from others—we are on the receiving end of the bounty around us. But, as we can infer from what happened to the civilization on Easter Island, resources run out if they are not replenished. Asteya is the friend who taps us on the shoulder and says, “You must return what you take.”

Perhaps the simplest way to start our practice of asteya is with the Earth’s resources. We can move to a zero-waste lifestyle. We can reduce our carbon footprint, recycle, collect rainwater, and use solar power. We can share the land, rather than covet it for ourselves. We can repair our possessions rather than buy new ones.

As we peel back the layers of asteya, we also start to gain insight into why we take. What about that book we borrowed from a friend last year and didn’t return? Were we concerned we wouldn’t be able to do without it? And what about those two pairs of jeans we purchased instead of just one? Swami Satchidananda says that buying more than we need counts as stealing things “by not letting others use them.”

Often as spiritual seekers we are told to have faith that everything we need will be provided, yet here is asteya telling us not to take and take because resources will run out … How can both be true?

Asteya does not only pertain to material objects. It also points to the myriad of ways we steal with our time, words, and thoughts. How often do we take from our employer by not working when we are paid to do so? How many times do we steal from our friends with our words when we do not let them speak about their triumphs without chiming in about our own? How frequently do we steal with our thoughts when we envy those around us—taking away their right to joy?

And finally, perhaps the greatest victim of our habit of “taking” is ourselves. “In all the ways that we impose an outside image of ourselves onto ourselves, we are stealing from the unfolding of our own uniqueness. And all the demands and expectations that we place on ourselves steal from our own enthusiasm,” says Deborah Adele, in her book, The Yamas & Niyamas. The biggest theft of all is that, in our constant rush to achieve, she says, we take away our chance to enjoy the present moment.

Asteya offers us the gift of abundance. Often as spiritual seekers we are told to have faith that everything we need will be provided, to trust in an abundant universe … Yet here is asteya telling us not to take and take because resources will run out … How can both be true?

Because abundance, asteya teaches us, is not a one-way street. It is not, I will be provided for. It is we will provide for each other. Abundance is a circle. Furthermore, it is a growing circle, and we each have a role to play within it. Asteya teaches us that the more we put in, and the less we take out, the greater the abundance will be for all. Like this we can change the present, and rewrite the future so that the generations that follow us will never be lacking.

Anthropologists do not know for sure what happened to the Rapa Nui inhabitants of Easter Island. Some claim that in spite of using up the island’s resources, the generations that followed muddled through for many years by eating rats.

But if we adhere to asteya, we will hopefully never find out for ourselves.

4 Ways to Put Asteya Into Practice

1. Give Back

We can replenish the world by giving back time through volunteering, or recycling that which won’t be used. We can give away the clothes we don’t wear or the food that is unused in our pantries. And we can return all the things we have borrowed to their rightful owners.

2. Gratitude

If we lived in gratitude, we could never take without replenishing. When the trees have sheltered us from rain, how could we not wish to make sure they stay standing? When we experience the peace from giving ourselves a moment to be present, why would we continue to push ourselves at an unrelenting pace?

3. Generosity

According to the Buddhist texts, the antidote for stealing is generosity. Every opportunity you have to give? Give. At some point you will settle the score for all you have taken, so cherish every chance you get to be generous with your words, possessions, and heart.

4. On the Mat

We’ve paid our class fee. We’ve bought an eco-friendly mat and a reusable water bottle. Perhaps we have gone as far as to switch our spandex for hemp, and to rock a crystal deodorant instead of one with chemicals. But the greatest way we can bring asteya to our practice before we even begin, is by dedicating our practice to others. Not everyone gets to do yoga. We can offer up a prayer that they may too receive all the fruits that we receive.

During our practice, we are abundant with opportunities to stay in the mindset of not stealing. We can allow ourselves the full experience of every asana without worrying about the next chaturanga. We can let go of envious thoughts about the person in front of us who is nailing their eight-angle pose. In our savasana, we can silence ourselves from yawning or fidgeting so as not to steal another’s chance for enlightenment.

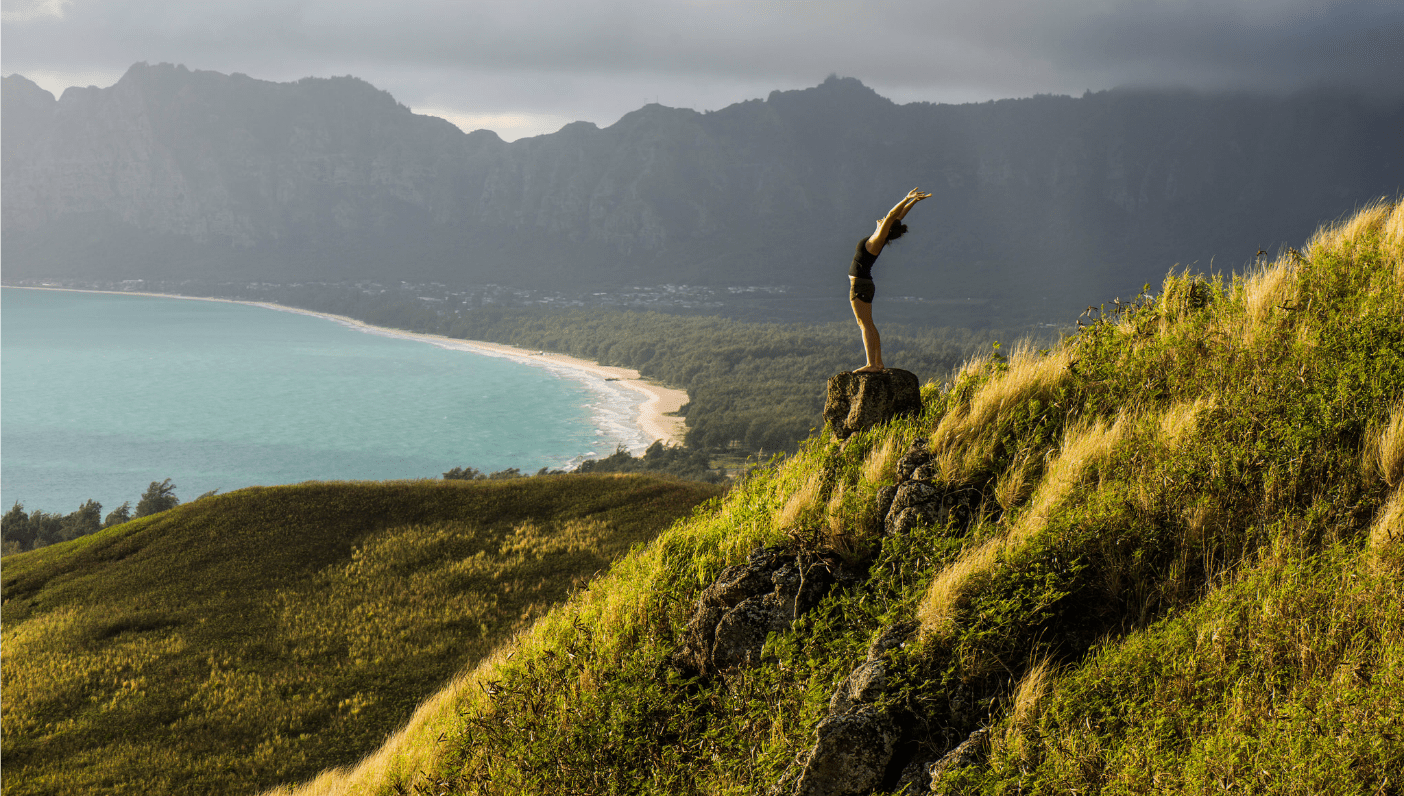

A great posture to cultivate asteya is Adho Mukha Virasana (downward facing hero pose). Here we become the hero who has returned from our quest laden with trophies and accolades, yet we take this moment to give away all of our boons, and bow to the Earth. For was it not for the Earth supporting us, we would never have been victorious. How can we ever repay her?

Join us next week as we explore the fourth Yama, brahmacharya: moderation.

—

Helen Avery is a senior writer at Wanderlust. She is a journalist, writer, yoga teacher, and full-time dog walker of Millie.